This year has seen an enormous increase in the number and claimed impact of hacktivist attacks on critical infrastructure and enterprises operating in critical services. Many attacks target unmanaged devices such as Internet of Things (IoT) and operational technology (OT) equipment. Attacks are motivated by geopolitical or social developments across the globe, with the goal of spreading a message or causing physical disruption. Targets of such attacks include steel plants in Iran, a military vehicle repair facility in Russia, gas pumps in Israel and programmable logic controllers (PLCs) in the U.S.

These examples, and many others discussed in Vedere Lab’s new threat briefing report, should serve to dispel the myth that hacktivists are a minor nuisance. Rather, this type of threat actor has considerably expanded their arsenal – and reach into unexpected industries such as telecommunications and retail. This is possible because of the widespread use of IoT and OT equipment – such as uninterruptible power supplies (UPSs), VoIP, building automation controllers and energy measurement devices – in almost every industry nowadays.

In the report, summarized here, we describe examples of active hacktivist groups; present the device types, specific models and protocols these groups have targeted; discuss their tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs); and provide mitigation recommendations.

Relevant hacktivist groups and targets

Several hacktivist groups have targeted unmanaged devices in 2022. Examples include:

- GhostSec has been active since 2015. It includes members from several countries and does not have a single political agenda. Their operations involving unmanaged devices in 2022 targeted Israel, Russia, Iran and Nicaragua. Organizations attacked were in industries as diverse as retail, telecom, hotels and utilities. Devices identified in these attacks include SCADA, HVAC controllers, energy measurement and several programmable logic controllers (PLCs). These devices were attacked either via their internet-accessible human-machine interface (HMI) or by directly interacting with insecure protocols such as Modbus using custom-built scripts and publicly accessible Metasploit modules.

- Team OneFist was founded in March 2022 by a group of international hacktivists. They are a pro-Ukrainian group and work in close collaboration with other similarly aligned groups. All their targets were located in Russia and they focused on infrastructure organizations, especially in sectors such as telecommunications, utilities and manufacturing, with the goal of denying availability of services or causing physical destruction. The group attacked specific internet-accessible device types such as UPSs, SCADA, network routers and VoIP equipment. Besides changing parameters via the user interface, Team OneFist also defaced these HMIs with pro-Ukrainian and anti-Russian messages, and they often wiped data on devices.

- Gonjeshke Darande, also known as Indra or Predatory Sparrow. On June 27, the group attacked three Iranian steel plants and released a video that shows a fire breaking out at the facility as the supposed result of the attack. This group has been active since at least 2021, when they attacked the Iranian railways, causing train delays and cancellations, and the Ministry of Roads and Urban Development, causing the national fuel payment system to go offline. Due to the sophistication of their attacks, some researchers believe the group is a state-sponsored, possibly military, organization disguising their true motivations as hacktivism.

- SiegedSec attacked Rockwell PLCs in the U.S. using the Metasploit Multi CIP module as part of #OpJane, a hacktivist operation against the overturning of the federal right to abortion in the U.S. The group is closely related to GhostSec.

- AnonGhost, another group protesting the war in Ukraine, hacked Russian devices such as street lighting systems, Moxa OnCell Ethernet IP gateways, satellite interfaces for navigation systems, SCADA systems at power stations, IP cameras and printers.

- Network Battalion 65 (NB65) is yet another group that targeted Russia. Some of their operations include hacks on IP cameras and several open SCADA systems. Beyond attacks on critical infrastructure, NB65 has been very active in leaking sensitive files from Russian targets and even using the leaked Conti ransomware against several companies.

- Anonymous, one of the oldest and most well-known hacktivist collectives still active, targeted Russian IoT equipment soon after the invasion of Ukraine. Examples include hacked printers mass printing Tor installation instructions and IP cameras hacked to show live video feeds of Russian military personnel.

Organizations and devices targeted by hacktivists

In most cases, hacktivist attacks are opportunistic, focusing on a country and sometimes a sector, rather than on a specific organization. Once the initial target scope is defined, some groups focus on large-scale attacks by finding similar device models in several organizations and attacking them at the same time.

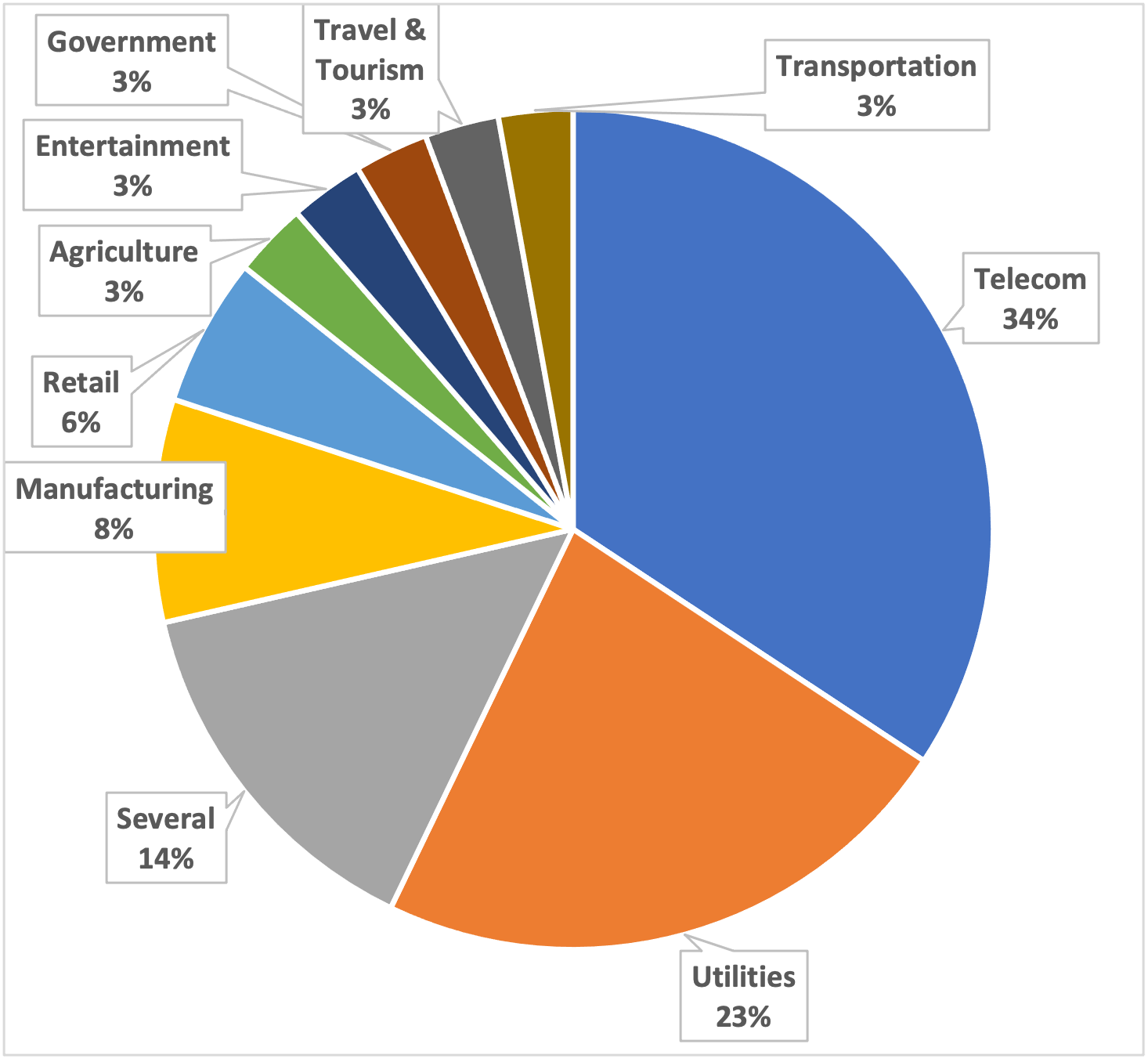

As shown in Figure 1, threat actors have been targeting unmanaged devices in organizations not only in traditionally OT-heavy industries such as utilities and manufacturing but even more so in unexpected industries such as telecommunications and retail. This is possible because of the widespread use of IoT and OT equipment – such as UPS, VoIP, building automation controllers and energy measurement devices – in almost every industry nowadays. Organizations that are not typically considered critical infrastructure rely on much of the same equipment but may have less knowledge or fewer regulatory obligations to protect those devices.

Figure 1 – Most targeted industries

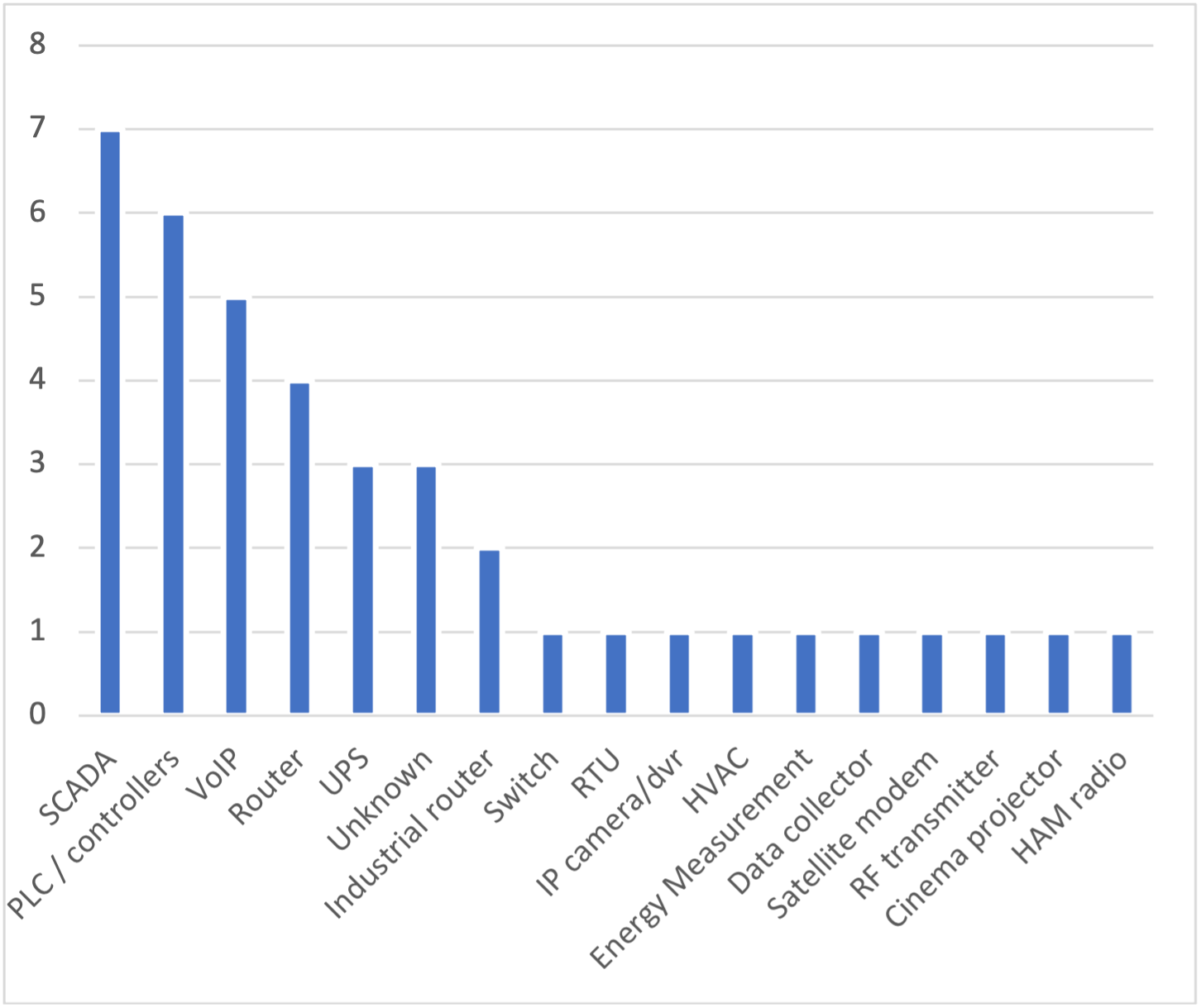

Within these organizations, the most targeted devices are shown in Figure 2. The most popular were SCADA systems and PLCs, followed by networking and VoIP equipment, then UPSs. Attackers showed a preference for device models that are popular on targeted environments and can be fingerprinted over the internet. They seem to attack the same device models repeatedly.

Figure 2 – Most targeted devices

Tactics, techniques and procedures used by hacktivists

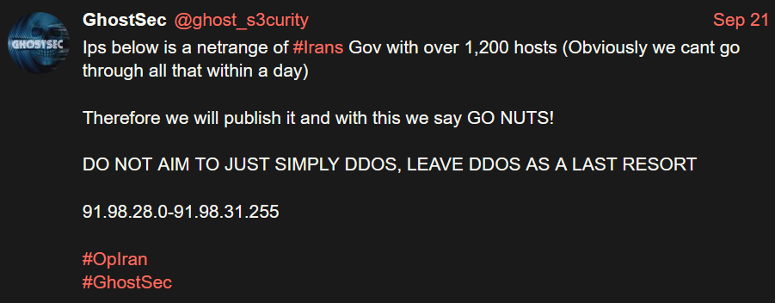

The main recent evolution in terms of TTPs for hacktivist groups has been a shift from distributed denials of service (DDoS) to damaging targeted organizations by exploiting their unmanaged devices. Figure 3 shows an example of GhostSec sharing target IP addresses and inviting their members or sympathizers to “leave DDoS as a last resort.”

Figure 3 – GhostSec inviting attackers to “not simply DDoS”

The table below details the TTPs observed by the groups we reported, giving specific examples of procedures. Some techniques, such as Automated Exfiltration, are not in the table because they were not directly observed in the groups’ communications, but it is safe to assume that they are performed. Since these attacks mainly focus on internet-accessible unmanaged devices and are not prolonged campaigns that aim to remain undiscovered – as is the case of advanced persistent threats (APTs) – several tactics are either not necessary or rarely executed, such as Persistence, Privilege Escalation and Defense Evasion.

The veracity of claims about attacks that cause T0828 – Loss of Productivity and Revenue and T0879 – Damage to property is very hard to ascertain. Even when attacks happen, often industrial facilities have safeguards – such as control logic with sanity checks on parameter values, safety instrumented systems and interlocking – that prevent catastrophic effects from happening due to malicious interaction with industrial equipment. In other cases, the malicious interaction itself may be immediately overwritten by a legitimate transmitter writing to the same variable that was just modified by the attackers.

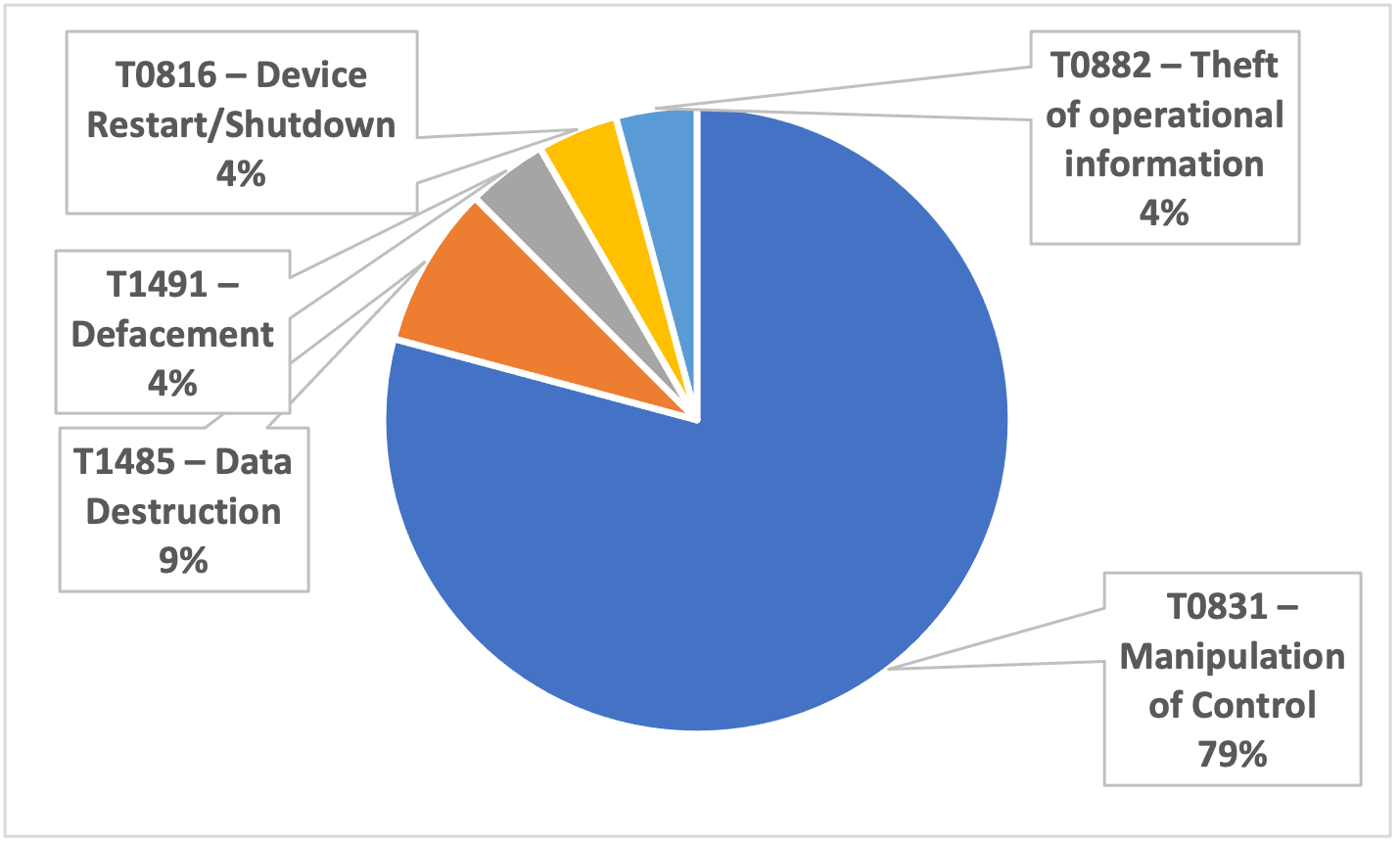

The most common techniques observed directly on the incidents listed in our report are shown in Figure 4. The vast majority of the incidents (79%) achieved impact via T0831 – Manipulation of Control, which in turn was realized by modifying parameters via the HMI/GUI (in 85% of the cases) or via Modbus (in the remaining 15% of cases).

Figure 4 – Most observed techniques

Mitigation recommendations to ward off hacktivist attacks

Considering the increased scope of hacktivist attacks, cyber hygiene practices such as hardening, network segmentation and monitoring must be extended to encompass every device in an organization, not only traditional, IT and managed devices.

- Harden connected devices. Start by identifying every device connected to the network and its compliance state, such as known vulnerabilities, used credentials and open ports. Change default or easily guessable credentials and use strong, unique passwords for each device. Disable unused services and patch vulnerabilities to prevent exploitation.

- Segmentation. Do not expose unmanaged devices directly on the internet, with very few exceptions such as routers and firewalls. Follow CISA’s guidance on providing remote access for industrial control systems. Segment the network to isolate IT, IoT and OT devices, limiting network connections to only specifically allowed management and engineering workstations or among unmanaged devices that need to communicate.

- Monitoring. Use an IoT/OT-aware, DPI-capable monitoring solution to alert on malicious indicators and behaviors, watching internal systems and communications for known hostile actions such as vulnerability exploitation, password guessing and unauthorized use of OT protocols. Monitor large data transfers to prevent or mitigate data exfiltration. Finally, consider monitoring the activity of hacktivist groups on Telegram, Twitter and other sources where attacks are planned and coordinated.

For a deeper dive into these hacktivist groups, targeted industries and devices, TTPs used in each attack, and mitigation recommendations read the full report.